Best practices in mentoring: teachings from

experience

|

Chair | Michelle Effros, Cal Tech |

|

Panel |

Vincent Poor, Princeton University |

|

| Bob Gray, Professor and Vice Chair of EE, Stanford |

|

| Jeff Koseff, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering, |

|

| Stanford |

|

|

While we recognize that mentoring is a two-way process, this session

focused primarily on best practices for mentors, leaving questions of

how to

find good mentors and be "more mentorable" to later sessions. The

purpose

of these remarks is to provide a brief statement and overview of

some talking points that are of interest in the context of mentoring of

engineering students and faculty. After a few general observations on

the

nature of mentoring, some issues arising in connection with various

stages

of mentoring will be mentioned. Finally, some specific issues that are

of particular interest in the mentoring of women engineering students

and

faculty will be discussed briefly. All of the issues raised here are

discussed in greater depth in other sessions of the workshop, and these

brief comments are intended only for the purpose of raising issues, and

are specifically not intended as the final word on any subject.

It should be taken as axiomatic that mentoring, which involves many

complexities of personality and inter-personal dynamics, is more of an

art

than a science. A corollary to this axiom is that there may be as many

"best practices" in mentoring as there are mentor-advisee pairs.

However, as with other arts, we can still certainly look for general

principles of good mentoring, which of course was the purpose of this

workshop. As with other arts, reasonable people can, and will,

disagree on what constitutes good mentoring practice. (Not the least of

the factors contributing to such disagreements is the fact that the

trajectories of successful academic careers are quite varied.) A

related

issue, sometimes overlooked, is that the personality, aspirations and

career

stage of the mentor are major factors affecting the mentoring

process. So,

in looking for good mentoring practices, we should not lose sight of

these

human dimensions.

Given that good mentoring styles can vary enormously with personality

type

and that most faculty are not trained to mentor, many faculty learn

about

mentoring through personal experience and observation. Observing both

successful and unsuccessful mentoring styles and then attempting to

apply

the lessons learned there is a useful part of the process. The role of

a

mentor includes directing and advocating, evaluating and rewarding,

celebrating successes and guiding through adversity and disappointment.

Some basic underlying principles to keep in mind in developing one's own

approach to mentoring include:

- Credibility

- The better we are at what we do, the better mentors

we

will be.

- Integrity

- It's not enough to talk about integrity, one must live

the

example. Many students do not take it seriously. Mentors must.

- Confidence

- Many students start with little but can become

outstanding

when properly encouraged and appreciated.

- Cooperation

- Discourage aggressive competition among students.

Encourage

cooperative efforts and openness.

- Chores and citizenship

- Engage students in professional

responsibilities:

reviewing, proposal writing, presentations,

mentoring. This does

not mean handing these tasks off and letting

them sink or swim. It

means, for example, having a student write a review

and then writing

your own. Let them see how it changes. Give them

the opportunity

to learn all of the skills they will need later in

their career.

- Communication skills

- Brilliant research is of little use if not

understood.

Correct English with good style is critically important.

Practice

writing and speaking skills constantly.

- Professional Activity

- Send students to conferences to attend and

give talks.

Rehearse them extensively. Introduce them to colleagues. Get them

plugged in. After graduation, recommend them for program

committees,

technical committees, reviewing chores.

- Credit

- Give credit generously to students. It helps them and

makes you

look good.

- Sharks

- Although many institutions have programs for diminishing

sexual

harassment, it still exists. Be sensitive to potentially

embarrassing

or dangerous situations and do not accept inappropriate behavior

from

colleagues towards your students. Institutions should have a

zero tolerance policy

towards any mentors who abuse their position.

While many of these points may seem obvious, they are not generally

recognized.

|

|

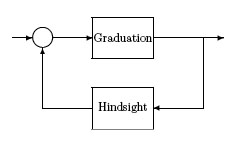

Feedback

|

Learning to mentor is a process of continual learning, rethinking, and

revision.

Feedback is a critical element in developing good techniques for

mentoring.

One way to measure success is to track the careers of one's former

students.

Mentoring does not stop with a degree. It is a life-long relationship.

Students evolve into colleagues, and staying in touch with these

colleagues can

be useful to both former students and their former advisers. Remaining

accessible

to former students allows a mentor to benefit from their hindsight and

provides a

mechanism for gathering and promulgating successful techniques.

Further, since

former students often lack mentors at new institutions, maintaining the

mentoring

relationship can also be of great importance to former student's

continuing

development. Also, visits from alumni provide wonderful contacts,

examples,

and sources of information and inspiration for later

generations

of students.

A variety of desirable attributes of mentors were suggested during

discussions:

- Use a light touch.

- Be patient.

- Be supportive and encourage goodness and provide direction when off

the

rails.

- Try not to mess the students up, they came in as good

students. A variation on

the Hippocratic "do no harm."

- Discuss the skills needed for prospective new faculty members,

such as

negotiating initial start-up packages and initial teaching

responsibilities.

- Try to teach the skills that often confound new junior

faculty, such as completing

merit reviews, preparing proposals, choosing committees, and

selecting good graduate students.

- Some students need little mentoring, but it is not good to

ignore them. Everyone

can benefit from encouragement.

The following paragraphs contain some brief remarks on the main

mentoring

objectives and needs for advisees in various stages of academic careers:

graduate school, untenured faculty positions, and senior faculty

positions.

The objective here is not to be comprehensive, but rather to touch on

only

the principal issues.

Graduate school is essentially an apprenticeship for learning to do

research. The main objectives of graduate students are to learn to do

creative, leading-edge research, and to publish it to the research

community through conference presentations and journal articles. The

main

things that graduate students need to do this are the freedom to be

creative (a lot of it), encouragement, patience and opportunities for

confidence-building through progressively public and formal forums in

which

to present their work. Obviously, mentoring of graduate students is

performed primarily by research advisers (although post-docs and other

faculty can of course play roles as well), and the primary objectives of

mentors should be to provide an atmosphere that encourages individual

creativity, and that offers opportunities for students to develop

communication skills.

An untenured tenure-track faculty position is essentially an apprenticeship for

learning to be a professor. Junior faculty members are in much greater

need of mentoring than are graduate students, for several reasons:

- Junior faculty members have much more complex jobs, involving

course

preparation and development, teaching and evaluation of classroom

students,

supervision and advising of research students, setting research

directions

and raising research funds, and participating in departmental and

university governance. Most of these jobs are completely new to

assistant

professors.

- Junior faculty members are typically at an age when they need

to begin achieving a balance between work and outside life. Often being

out of school for the first time in life, it is a time when family and

other personal obligations and interests begin to increase.

- Unlike the situation in graduate school, there is no well-defined

"curriculum" for successfully accomplishing the job of a junior

faculty

member; i.e., the rules are not formalized.

- Many junior faculty members have no formal mentor or adviser.

Although

some departments do set up a mentoring system, it is not universal, and

there may be conflicts of interest that do not really arise in the

professor-student relationship.

- The environment that junior faculty members find themselves in may

not be

supportive or even benign. Departmental politics often affect even

apolitical faculty members.

So, this stage of mentoring is perhaps the most important one, and the

one that deserves the most attention.

Untenured faculty members need to focus their efforts on two things:

building a visible, independent research program, and being a good

classroom teacher. Although there are of course many dimensions to

this job, these two are essential for achieving tenure at most

universities. Aside from emphasizing the importance of these two

objectives, mentors of young faculty members (and such mentors include

former professors as well as senior colleagues) can help them in

practical ways such as sharing of successful proposals as exemplars,

sharing proposal-writing advice, sharing of class notes, providing

introductions to senior colleagues and program managers, and extending

invitations to participate in workshops, special sessions at

conferences,

etc.

Although sometimes forgotten as targets of mentoring, senior faculty

members are still in need of advice and support on issues such as

career advancement and recognition. Here, a mentor can help with

things like nominations for positions of responsibility in academia or

scientific organizations, nominations for awards, and simply providing

encouragement and reassurance when needed.

One thing to note about mentoring at this stage is that it is usually a

two-way street, as the distinction between mentor and mentee tends to

blur with time.

While the above comments apply to mentoring generally, there are some

specific issues that arise specifically in the mentoring of women

faculty

members. (Some of these comments also apply to other under-represented

groups. However, they are phrased here in the context of women,

primarily because of greater experience with women.)

First, with regard to the mentoring of graduate students, experience

shows that differences in personality and ability are much more

important

than differences in gender, ethnicity or national origin. Thus a good

practice in mentoring graduate students of all stripes is to treat all

students the same, recognizing differences only in the former two

qualities

i.e., personality and ability.

As with mentoring in general, untenured faculty status brings perhaps

the most sensitive issues for women, namely tokenism and child bearing.

Since the number of women faculty members in engineering is

still relatively small, women tend to be asked (even while still

untenured) to take on a greater service burden than are men faculty.

Although this is driven by the admirable goal of providing diverse

opinions on key committees, it can adversely affect the progress of

junior faculty members in establishing successful research programs.

Some service is of course expected from all junior faculty, but women

faculty need to be especially careful in not becoming too immersed

in such matters before tenure. As has been noted, this phenomenon can

also provide opportunities for young faculty to meet very senior

university administrators. But, this often does not help at tenure

time, and so some caution is needed. A mentor can be very useful here in

helping junior women faculty members navigate these waters. Even when not asked,

women usually form a small minority subgroup of whatever faculty group they

find themselves in, including faculty meetings and informal discussions. Being in a minority

can make all actions more visible and put added stress on individuals.

A second major issue, and perhaps the most critical

issue for women faculty members, is the potential conflict between

the biological and tenure clocks. The tenure system that we have

today was established in the days when most professors were men,

and does not really recognize this issue adequately. Although many

universities now extend the tenure window for faculty members who

take parental leave, this still does not fully address the issue.

The role of the mentor is not clear here, since this is clearly a

very personal issue. However, as with much good mentoring, simply

providing information about various options and also providing

introductions to others who have been through the same decision-making

processes can be of help. This issue is treated in some depth

in chapter *.

Finally, with regard to senior faculty, a significant issue with women

faculty is the "imposter syndrome," the subject of

chapter *.

While this phenomenon is, of course,

not restricted to women faculty, it seems to be voiced more often by

women.

Here, again, a mentor can help by providing reassurance and help in

advancement and recognition, although as considered in

chapter *, recognition does not always relieve the

feelings

associated with the imposter syndrome. So, again, here is an issue

that requires particular attention.

In summary, the above remarks are intended to help frame more in-depth

discussion of the general issues arising in the mentoring of academics

at various career stages, and also to raise some issues that are of

particular concern in the mentoring of women (and other

under-represented

groups) in engineering academia.

May 9, 2005